Postal Failure

Published @ The Moving Arts Journal

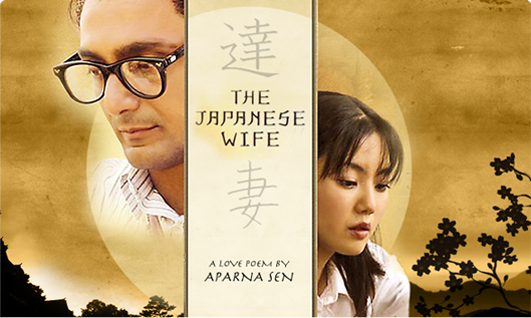

Poster of The Japanese Wife, 2010

Indian indie favourite Aparna Sen’s new film The Japanese Wife, about love through letters, lacks style and diction.

THE phonetic possibility of her surname Sen makes Indian indie filmmaker Aparna Sen’s films a fine fodder for all sorts of rhetorical puns in English, most obviously for a word, like say, sensational. But sadly her latest outing The Japanese Wife does not lend itself to the word because the film is anything but an Aparna Sen film. This also means that many of her previous films actually do lend themselves to hyperbole and it is incumbent to look closely at them individually, which, given her sparse filmography, is not a difficult task at hand. Only such a critique will best highlight why her latest is simply not up to the mark. Otherwise, the author remains a huge admirer of Sen’s abundant sensibility as a filmmaker, which makes her deserving of a seat among global auteurs, perhaps more than any other Indian filmmaker.

Her two early films, 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) and Parama (1984) vowed a generation of intelligent audiences with their sharp evocation of the margins of Bengali middle class life and at the same time created a new audience for intelligent cinema among her own generation. Opinion is divided, but she is often said to be the most accomplished heir to Satyajit Ray’s illustrious legacy as well as that of her father Chidananda Dasgupta, a pioneering film critic.

The acclaimed 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) is now a bonafide classic, a poignant meditation on the loneliness and longing of an Anglo-Indian schoolteacher in late 70s Calcutta whose earning for company leaves her soul open to be trampled upon by a sophisticated young Bengali couple desperate to steal some time in pre-nuptial bed, away from the roving eyes of the middle class moral panopticon. Lane stunned audiences worldwide and announced the arrival of a major talent in cinema. Sen, then in her mid 30s, was already a popular actress in Bengali cinema and had, with Lane made a successful transition to filmmaking with the multiple award-winning film starring Jennifer Kendal in her role of a lifetime. She followed Lane with Parama, a bold and severe critique of the coda that Calcutta’s middle class surrounded themselves with and how that chocked the desires of a woman desperate for affection and love from a man who can stand by her.

In Lane, Violet Stoneham’s (Kendal) marginality and obligatory solitude was only reinforced by the pretensions of the Bengali couple who promised her company. In actuality, Violet was a leftover from her own community — the Anglo-Indians– who had, shaken by the violence of the city (Calcutta) of their keeps and its diminishing cosmopolitan and industrial returns, migrated en masse out of it, leaving lonely and vulnerable sensitive little specimens open to further humiliation and decrepitude. Such specimens included Violet and her elderly brother who is seen bitterly raging against the dying of the light and cultures throughout the movie. Shunned by her own people, Violet was looking for affection among others in the changing demography of a once-multicultural city, while Paroma was doing the same among her own people, who by now had come to make Calcutta in the shape of their own. No wonder we see early 80s Calcutta increasingly finding its progressive and internationalist lineage superceded by the docile, dogmatic and impertinent provincialism of Bengali middle class. Both Lane and Parama ripped open into the Bengali middle class’ problematic negotiation of private morality and saw through the gratuitous underbelly of public consciousness. In short, the films were bold, uncompromising and bared the endemic and systemic psychic violence of middle class life in Kolkata.

Sen returned to this theme fifteen years later with Paromitar Ek Din (House of Memories) in which cultures and moralities collided again, though this time the violence is redeemed by an extraordinary friendship between two women, both battered in their own ways and happen to be related by law, who find ways to connect with each other across very dissimilar socializations and age. The quiet but assured rebellion of the two protagonists, a woman and her mother-in-law, showed a mellowed if maturing filmmaker now helming the baton. From Paroma to Paromita, Sen clearly progressed to discover how diverse and conflicting social stocks, endowed with a little individualism, can come together to create piquant spaces of comradeship in an otherwise severely demanding moral universe of the middles class.

With the exception of Sati, a telefilm, Sen made just one feature film – Yugant (What the Sea Said, 1995) –between Paroma in 1984 and Paromitar Ek Din in 2000. Yugant is a hugely underrated film whose hypnotic power continues to overwhelm this author, for whom the film remains and will always remain a tall mention in his catalogue of all time favourite celluloid gems. Yugant is about an estranged couple who meet several months after their estrangement at a faraway beach somewhere on the Indian East Coast to make an effort towards reconciliation. The location is carefully chosen as this beach and their rest house is the same one that the refined, artistic couple had honeymooned in several years ago. No wonder they had now banked, among an assortment of tangible, intangible and mnemonic assets, on the sea’s consummate powers to wash away the distance that had ballooned between them, hoping that the sea would return their faith. But within a day of their visit they realize that the sea, now hopelessly corrupted by oil from the Gulf War (a phantasmagoric but haunting motif) had lost its transcendental, pre-Lapserian powers of healing. Against their prayers to help them overcome the endemic solipsism of urban conjugality and the faith entrusted by the local fishing community for collective good, the sea could only return dollops of oil hidden under its alabaster foam which, in a moment of climactic and catastrophic denouement, catches fire, overwhelming one of the protagonists irretrievably. The film’s dark but brilliant finale reinforced the film’s power as a brooding, surreal chronicle on the globalisation of violence, long before globalisation was to become a discounted word.

Her last two films before The Japanese Wife, both in English and made on comparatively bigger budget and canvas were very different from each other. Mr & Mrs Iyer (2002) is an incisive love story between a conservative Tam-Brahm girl and a Muslim wildlife photographer that unfurl itself on a perilous bus journey through the blight of communal carnage that snowballs from usual trivialities and tornadoes past them. The protagonists manage to survive the onslaught, while understanding each other’s typical and atypical subjectivities, in an otherwise impaling eco-system of betrayal and bestiality typical of communal outbreaks in India. Their ways eventually diverge, leaving both of them with the lingering feeling of love found and lost but not before they help preserve each other’s belief in humanity. Compared to Sen’s own standards, Mr & Mrs Iyer was simple, heartwarming and clichéd with many of the usual trappings of a wish-fulfillment and predictable feel good narrative. But it was still very believable. Few months into its release, the horrible Gujarat riots unfolded, giving the film a deserving aura of clairvoyance that added to its appeal and publicity.

The film was a critical and box office success and gave Sen access to a completely new audience in Indian cities outside Calcutta, an audience who had always considered her films too elitist to view with the disposition of watching a Bollywood film, a disposition that distinguishes the largest constituency of the cinema viewing population in this country.

Surely Sen had little to complain about finding a wider audience because any genuine filmmaker would want her films to be seen. But it is one thing to find an eager audience and something else to please them. So, in spite of finding new audience with Mr & Mrs Iyer’s Sen did not stray from her raison d’etre and pandered to their taste. Instead, she returned to filmmaking three years later with the audaciously cerebral 15 Park Avenue (2005). Seemingly an elegy, a difficult and complicated one at that, to those afflicted with schizophrenia, 15 Park Avenue nevertheless packed in the many trials of contemporary urban Indian femininities within a framework of the life of two half-sisters in a modern-day Calcutta. Torn between her own delusions and strong determinants of reality, Meethi (Konkona Sen Sharma), the schizophrenic younger sister, little sympathizes with the crisis of Anjali (Shaban Azmi, both superlative) who has put everything at her disposal at stake for her sister. A chance meeting with her ex-fiancé deludes and distances Meethi further into the dark. Increasingly she is unable to respond to anything other than the language of the conquered as she vehemently seeks to protect the innocence of Saddam Hussain in the Iraq War, while all through searching for the mythical address that titles the film. The US search for the elusive WMD mirrors Meethi’s search for the mythical address and in the trials of the besieged family the global blunderbuss of truth, lies and collective amnesia is played out to chilling effect. The last scene in which Meethi vanishes into her own delusions hunted by the imaginary address (and Saddam is captured on television), is, like Yugant, numbing and renders the deep abyss of schizophrenia, individual and collective, with unmatched authority. 15 Park Avenue was clearly a film that showed the maker at the height of her powers.

It is with such a bravura pedigree that Sen launched herself into making The Japanese Wife (2010). The first thing that differentiates Wife from all her previous movies, something which seem to have had a telling effect on the film, is that this is the movie that Sen adapted from a story by someone else (Oxford academic and author Kunal Basu’s short story of the same name), something she has never done before. All her stories are her own, a rare feat among cinema making cultures in this part of the globe.

This was a problem to begin with because throughout the film it seems that the director is unconvinced about the story herself, improbable as it is in any case. The story of a mathematics school teacher in remote Sunderbans falling in love with a girl across longitudes in pastoral Japan through letters, sustaining the improbable match and intangible affair, marrying her over couriered niceties and totems and remaining married for close to two decades without meeting her, demands a copybook suspension of disbelief. And the ability to achieve that sense of convincing disbelief that could make logic out of an improbable premise is sorely missing, both from the script and the making of the film.

Sen has repeatedly insisted while talking about the film that it was this implausibility of the premise that primarily drew her to the story but the film bears little signature of her claim of being besotted, however ennobling it may have been to her. This is not to say that the premise was defeating in the first place. Impossible love often makes great cinema and some of the more notable contemporary directors from the Balkans or West Asia, have made extraordinary films in which the premise is absurd, comic or illogical. Similarly, the stories of Latin American masters, from Marquez to Bolano, are often full of charming inanities but most often than not, they add to the appeal of the film or the story.

Unfortunately Sen’s film is a serious film to begin with. And in a serious film hinged to the absurd beauty of unmated love across oceans, Sen had to make the lived reality, the psychological, social and moral eco-system in the film very convincing, unlike in a comedy or satire where fantastic liberties with realism are often the norm. In other words, what is justifiable in contested landscapes and among people busy in real or imagined conflicts rendered through comedy or satire is often unattainable elsewhere, specially when the absurdity is laced with more than necessary sobriety, as with the Wife. The wild beauty of Sunderbans is unmistakable, its remoteness unnerving, the lives of its people in constant conflict with its ecology a potent backdrop for impossible lives, but none of it ends up justifying Sen’s weak plot peopled with stock characters, either stripped of regional manners or rendered labouriouly and most crucially, ending with a whimper.

She struggles with her latest because of her own lack of conviction as well as because of her inability to create any emotional locus for the film, a job she had mastered in all of her previous films. It is clear that the urbane director, whose films are rooted in complicated physiological and moral realism(s), was struggling with logic, a struggle that puts her intellectual certitude under strain. And the strain translates into faulty characterisation, forced dialogues and accent, stilted acting, caricature and other assorted ambiguities that the script is replete with. This way the film not only lacks her conviction but also her authority, her compassion for her characters and an intellectual ethic that made her earlier films so much more rewarding.

The film’s cinematography is one of its strengths but the wilderness of the backdrop ensures that it is not a difficult delivery. There are some fine moments of quiet beauty between the characters and without them, a wonderful use of ambient light, occasional sprinkling of well-wrought humour and the natural felicity of actor Raima Sen as an ensnared widow. But for a director of Aparna Sen’s calibre, these were to have been germinal and not the only takeaways from the film. With a lesser filmmaker The Japanese Wife could have perhaps been a simple and innocent ode to love that defies logic, place and cultural mooring, blossoms in unlikely places, attains an eternal halo among apparent strangers and ennobles and empowers ordinary humans living small lives. But Aparna Sen is somewhat of a stranger to bucolic simplicities and her films ought to be much more than just serene exchange of impossible loves. She is a mighty talent and her films, in their complicacy, urbanity, rebellion and redemptive power must do justice to herself.

comments for this post are closed