No saffron on the plate

Published @ The Indian Express

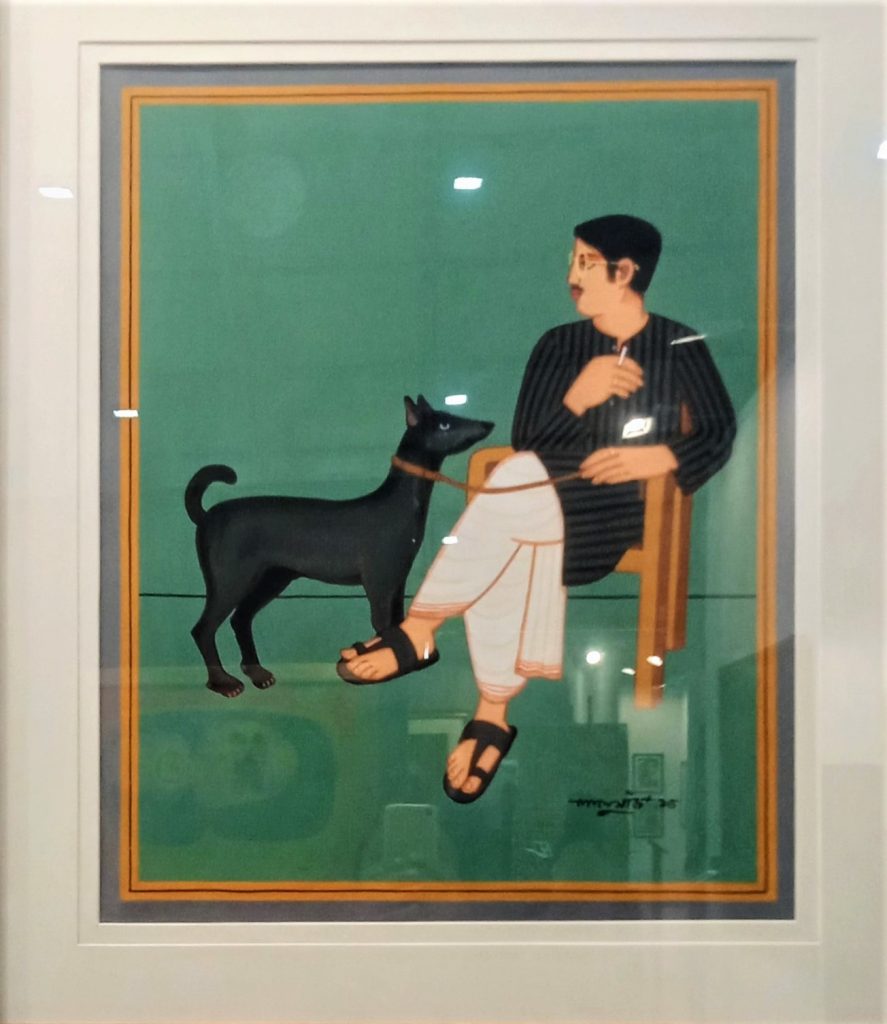

A painting by Laluprasad Shaw

It would be wrong to say that the BJP is taking the Left’s place in Bengal.

(co-authored with Anirban Biswas)

Jayanta Ghosal’s article ‘Among the believers in Bengal’ (IE, March 26) is so full of cocky generalisations and mistaken observations that it needs a riposte. To begin with, his argument bestows a monolithic identity on the “Bengali”, while using bhadrolok and “Bengali” as interchangeable nomenclature. To remind that within the overarching umbrella of the linguistic denomination, there are differing class, caste, religious and national identifiers which converge and diverge is to state the obvious. The bhadrolok is a small part of this convocation. Second, Ghosal draws a simplistic line of progression between the Bengali as once-communist and now a would-be communal. As if, the moment the Bengali bhadrolok gives up his socialist “pretences”, he automatically covers himself in a saffron cloak. This sort of binarism usually plagues political commentary on Bengal, conveniently omitting the attendant complexities. Ghosal’s essay is part of this flawed bequest.

Ghosal also makes an unsubstantiated claim about communism preaching atheism through its time in power. The communists sat easy on the dualism of everyday Bengali life, where effete, non-aligned spiritualism existed merrily with socialist hope. In fact, there were raging debates within the CPM about the scope of intervention in matters of faith. But the radicals never prevailed. To proselytise any kind of radical atheism, the communists had to first denounce their belief, which was never the case. So, Jyoti Basu’s god-fearing wife was not an exception but a convention in Bengali cultural life. Moreover, Bengal’s long tradition of arrogant Hindu evangelicalism, from Ramakrishna to Syamaprasad Mookerjee, as every critique of Bengali “renaissance” has pointed out, ensured that social reforms and homegrown spiritualism were cheerful bedfellows throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. To that end, even the most radical intelligentsia has never been at home in a godless world; nor have they made any moral or intellectual investment in conceptualising one. The Partition, riots and the insidious network of patriarchy and anti-modernity have, over a long period, ‘nourished’ the low self-esteem of the believing Bengali man. It is hence no great puzzle that a section of them are now scrambling to belong to a nationalised Hindu imaginary. But this desperation to belong is propelled by growing aspiration and consumerist appetite insatiable in a climate of limited economic opportunities; other than by any implicit faith in BJP’s temple-politics. Hence, the claim that communist-engineered repression of “natural” faith is now finding release in BJP’s alluring rhetoric is a gross exaggeration of political influence.

Ganesh Chaturthi and Dhanteras or sangeet ceremonies are less about cultural influences than being the levelling of differences to manufacture a pan-Indian, predictable consumerist pattern. To regard them as testaments to BJP’s rise, as Ghosal does, is to make the bizarre claim that the embrace of Valentine’s Day in 1990s was a marker of Christian takeover of social life.

In fact, a more serious economic logic is at play here. Trinamool’s great enthusiasm for umpteen “new” manufactured festivities across Bengal is well-known. When the subsistence economy is even marginally sated, there is a tendency to gravitate towards the leisure economy. In Bengal, this puny leisure economy is dominated by a procession of state-backed hyper-local fetes that also act as transitory spaces for political one-upmanship. These festivals are “valuable” in a state which has a miserable record in jobs and industry, pushing a large part of the workforce towards low-end informal employment. In other words, TMC’s “festivalism” camouflages precarity as well-being. A party as cunning as BJP knows that too well. Just like Ayodhya acts as a sedative in parts of North India, the pageantry of festivities in Bengal ensures an amnesiac indifference to crises. So, the apparent rise of “unfamiliar” celebrations on the Bengal soil is not so much about the ideological shift as it is about canny employment of leisure in political mobilisation; while keeping the gullible busy in gobbledygook. And to date, the TMC has managed it way better than the BJP can hope to in any near future.

All these factors militate against an easy assumption that Bengal’s changing cultural life directly reflects a rise in BJP’s political heft. But is there any heft to speak of? Ideological shifts are notoriously difficult to map in the short term but what can be gauged is if the BJP is evolving as political power — at the expense of a perpetually-squabbling Congress and an organisationally-tattered Left. It was only during the peak of the “Modi wave” that the BJP attained a vote-share of above 15 per cent, which went down recognisably in 2016 state elections. The panchayat elections show a similar graph and even at its peak, the vote share is unlikely to cause any flutter in the incumbent TMC. The CPM’s consistent downfall has been mined by the TMC and not the BJP. So much so for the shift from red to saffron. Even if there is relative tolerance for BJP’s rousing nationalist discourse among a section of urban middle-class, lower caste groups — once CPM’s playground — have stoically been aligned to the TMC. Ditto for the Muslims.

It is hence entirely in the realm of a hypothesis that the BJP is seen as an emergent force in Bengal — culturally or politically. The social engineering it has undertaken in border-districts will give it some sound-bite on slavish television and it will make the usual noises on social media. But the TMC hunts with the wolves and runs with the hare. So, good, bad, or ugly, it is here to stay. At least till Mamata Banerjee is alive and kicking.

comments for this post are closed