Aesthetic Enclosure and Insurgent Critique in Ray’s Fantasy Fables

Published @ Café Dissensus

To view the published version, see

Café Dissensus

|

PDF

1 Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1969, hereafter Goopy Gyne)and the follow-up fantasy Hirok Rajar Deshe (In the Land of Diamond King, 1980) are two parts of a trilogy of fabular musicals for children.[1] Or so is what they have been mostly, if not always, remembered as. Ray had often felt that films for children made locally were unable to satisfactorily capture their imagination. More often than not, those films sentimentalized childhood, or treated them as part of a sealed world full of over-virtuous creatures. So when Ray’s young son Sandip beseeched him to make a film that was less adult and adroit than his usual lot, it stayed with him. His son’s pleading, says Andrew Robinson, “chimed with Satyajit’s own desire to reach out to children by giving them something vital, original, and Bengali, which he felt did not necessarily mean having a child actor.”[2] This also meant going back to a familial commendation. As Robinson adds, “Goopy and Bagha released the pent-up love of fantasy in Satyajit Ray that is given free rein in his grandfather’s and father’s work… its inspiration comes from Upendrakisore, while that of The Kingdom of Diamonds derives more from Sukumar; its word play and juggling of ideas are much akin to his plays.”[3]

There is a problem, however, in seeing the two films exclusively as cinema for children, because both are deeply political in content and also context. In fact, Ray uses the fantasy form – abounding in an instinctive play of innocence, high-spirited musicality, and underdog triumph – to mount two substantial critiques about the absurdity of needless war, and the evil ministrations of fanatical totalitarianism. This is most meaningfully borne by the fact that Goopy Gyne is substantively different – in tone and tenor – from Ray’s grandfather’s story. Upendrakishore’s comic ghost fantasy, published in 1915, had a broadly similar plot but is without a shadow of politics. As for Hirok Rajar Deshe, the comic rhyming, witty puns, and alliterative compositions have the distinct presence of Ray’s father Sukumar, whose limericks, panegyrics, and poems were redolent with political insinuation. But Hirok Rajar Deshe is a much more candid censure of autocracy than Sukumar would typically allow to surface in his work. Moreover, GGBB is a film for children without children; and even if Ray amended this absence in Hirak Rajar Deshe, where children are equal stakeholders in the unseating of an autocrat, they are not central to the narrative.[4] Either way, both films imagine a child-spectator, in case they do, who is a sapient, sensitive, curious worldly being, would go out to explore a problem rather than flinch from it or escape into an artificial world without fissures. To that end, the films have a different temperament than any of Ray’s other works for children[5] (whether literary or visual); as much they are distinct from films for children generally. It is in this context that the use of the fantasy form in constructing an autotelic world punctuated by pernicious intrigue is critical, as is the germane tension between a fantastical imaginary and an entrenched political critique. These tensions become all the more pressing because Ray nimbly uses science and magic as interchangeable forms of enchantment in both the films. In fact, the access to the political stealth and satiric intent in these films lies through the triumphalist rhetoric of state-sponsored scientism and the unchecked access to propaganda that accompany phony wars, both testifying to Fascism’s perseverant lust for institutions of governance.

2 Goopy Gyne follows two tuneless performers who are chased out of their villages for being an annoyance. Exiled, hungry, and stranded in a forest one night, they are accosted by the King of Ghosts, who offers the guileless duo three gifts — of unchained melody, unrationed food, and limitless travel. Newly emboldened, Goopy the singer and Bagha the drummer string together their fellowship, hoping to put to good use their gift of freezing their listener into a stupor. Chasing the faint prospect of a royal residence and attention of princess, they land up in Shundi. Their full-throated, whole-hearted melody besot the king, who offers them his unhesitant hospitality. But Shundi comes under siege, for no apparent reason, from Halla – the kingdom ruled by the brother of Shundi’s king. Goopy and Bagha make secret visitations to Halla, learning that the childlike-king was kept enthralled in a Machiavellian delirium by his evil minister, with the aid of a cantankerous, shape-shifting magician. The king, when vulnerable to the magician’s medicated spell, turns raucously violent, announcing to execute anyone at the slightest show of ineptitude. The twosome is overwhelmed initially by the scheming minister but eventually manage to halt Halla’s marauding army of famished soldiers by showering them with a delectable array of edibles. The two kings are united and get their daughters married to the musician pair, who now emerge as a force of benefaction.

A decade passes by. Goopy and Bagha – sons-in-law to the king – otherwise contented with their life, long for a new adventure for fear of having their gifts fade otherwise. They readily latch to an invitation from a certain Diamond King to visit him as envoys of Shundi. Thus begins Hirok Rajar Deshe. Initially, the land of their host seems one of plenty with a benign king lording over it. The envoys also get a taste of the king’s lavish welcome. But soon they find that behind the façade of the generous king was a ruthless usurper, who exploited wealth extracted from the diamond mines. He had since grown into a corrupt and diabolic dictator who kept his farmers unfed and workers unwaged, disparaged education, free will, and dissent, and was reshaping the laws of the land to make him unassailable. But unlike Halla’s slaughter-happy king, the Diamond King did not threaten execution. Instead, his resident scientist, a smug inventor, had built a life-size apparatus where defaulters and dissenters could be shoved into, and indoctrinated permanently with the help of a hypnotic incantation. It is known as mogoj-dholai ghar – the brain-drilling chamber. On understanding the depth of the King’s wanton lust for power, Goopy and Bagha join forces with a fugitive schoolteacher as they amass their gift of music and magic (with a dose of stealing and bribing) to force the King and his minions into the drill-chamber, emerging from which they join hands to topple the king’s gigantic statue.

Clearly, both the films were way beyond the soft compassions of a typically children’s work, replete as they were with references to the Vietnam War and the Emergency (rather, the peril of unimpeded Stalinism), respectively. At the same time, they never leave the aesthetic enclosure of an imaginary world where magic, science, and music are conspicuously transposable. It can be safely assumed that this enclosure of the fantasy drew hordes of children to the theatres, most of them oblivious to the films’ undercurrent of political angst. In fact, Goopy Gyne became the longest running film in Bengali cinema history. This caught even Ray by surprise, as his letters to Marie Seton reveal. Fantasy apart, a major part of the success was due to Ray’s extraordinary compositions – earnest, tender, and hummable – which quickly became part of popular cultural reference and recall. The films do betray imperfections in production and design because of budget constraints, even if one must note that the performances of the main cast (Johor Roy, Rabi Ghosh, Santosh Dutta, Utpal Dutt) were outstanding.

3 The question is: what is this aesthetic enclosure? An aesthetic enclosure is not an aesthetic appreciation of a work of art but a way of understanding what Daniel Yacavone calls a film world[6]– the haptic and hermetic world that a film envisions (and constructs) inside it. In other words, the film world could be said to be a way of conceptualizing the diegetic world inside a film through its self-referential signifiers. To construct this world within, each film genre establishes a relationship with the world it aims to represent – science fiction, crime, noir, melodrama et al. So does fantasy. Ray uses the most obvious genre-specific portent of fantasy – that the action and setting refers to an alternate world – a sort of parallel universe as it were. As Jack Zipes says in a recent essay about the historic expectation from fantasy, “It is through fantasy that we have always sought to make sense of the world, not through reason. Reason matters, but fantasy matters more. Perhaps it has mattered too much, and our reliance on fantasy may wear thin and betray us even while it nourishes us and gives us hope that the world can be a better place.”[7] This is as basic an expectation from a genre as is, say, the element of surprise in a crime novel. Surely, like all genres left to the mercy of Hollywood, fantasy has got ever bigger and thornier than its history would otherwise recommend. But Ray’s reliance on the form was clearly on the simpler aspirations of the genre, to which Zipes points towards.[8]

By choosing to stay within the fundamental expectations of fantasy, Ray is not attempting to transcend the form. Rather he makes use of an unmistakable motif to enact, as it were, the aesthetic enclosure – the intervention of the ghost. Ghost stories have a long history in Bengal and even a cursory glance at its literary appearances would reveal their proclivity towards a comical poking of their spectral noses into worldly affairs rather than subjugating the hapless humans to horror. As Ian Almond says,[9] “The Bengali word for ghost (bhut)…has little to do with the Western image of the ghost — less a posthumous echo of the living, more a broad collection of varied, independent entities (headless ghosts, child-haunters, flying vampires, even harabhootor ghosts that try to drown people…” So, the ghost story framework gave Ray a familiar template to help situate his political fable away from a lived-in world of his audience. In keeping with the Bengali convention, ghosts in Goopy Gynepeacefully occupy another world, are of various demeanors, stature, and physical manifestations,[10] and show up in nocturnal time in forlorn forests. Most crucially, their benign intervention is the portal of passage for the twosome into the enclosure of fantasy. The ghosts are the usherers-in-chief and grantors of windfalls but play no role once that transition is made. Moreover, once Goopy and Bagha move into the other world made possible by the ghosts, Ray forgoes the clichés and caricatures of fantasy – gods, angels, creepy creatures, other-worldly landscapes, demarcated agents of good and evil, and so on. Rather, the apparently fantastic world is peopled with symptoms of the realpolitik – war-mongering ministers, smiling assassins, gluttonous power-brokers, wicked sovereigns and, most noticeably starving, voiceless, vanquished subjects. Nowhere is the depth of dissonance within the fantastical enclosure more conspicuously revealed than in the figure of the magician masquerading as scientist. Both Halla and the Diamond Kingdom perfect the art of suppression and manufactured consent through a perverse use of spells and charms. In Goopy Gyne, the evil minister is consistently dependent on the chequered-robed, long-bearded Barfi for all his misdeeds. Barfi is the fabular super-magician – speaks a gibberish language, offers alchemic medications, is solutionist on call, and an amoral mercenary on hire. His powers stem from him having access to a special form of knowledge. This character is a Ray invention (absent as it is in the source story) even if Ray dithers calling him a scientist. In Hirok Rajar Deshe, he doesn’t. Here, the more mediocre figure with a similar function of embalming power with technological gobbledygook is named as a resident mastermind, who is greedy, vulnerable to chicanery, and offers his services unequivocally to the king, in full knowledge of his malicious intent.

Ray’s inventive genius leaves no scope to misinterpret that he is deliberately creating the simulation of an enclosure – a self-referential film world – that severely mirrors his own. In fact, one can even claim that Ray is sabotaging the fantasy form with what in German is called weltschmerz – a lassitude, a recognizability of the lived-in world. Ray is distressed by the war in Vietnam (or any war for that matter), and later by recurring instances of violent devaluation of democracy and liberalism (from Augusto Pinochet to Indira Gandhi). It was natural for him to aim a severe critique of warmongering and despotism. But he is acutely conscious of political critique within the realist tradition, which tend to betray the liability of enforced resolutions. It is precisely why Ray had displayed a recondite insistence in avoiding narratives of Partition or any of the obvious political fissures of Nehruvianism, preferring to offer a quiet but interrogative appreciation of Indian modernity. By late 1960s, however, Ray’s patience was running thin. But he still did not want to fall into the artless trappings of a loud political statement. He chose the fable form. When Halla’s king is free of the spell and raves for having found release from the prison-house of power; or when the brain-drilled dictator joins in the celebration of his own downfall, Ray’s insurgent symbolism is all the more apparent. In other words, Upendrakishore’s ghost fantasy offered Ray the perfect narrative trope to take umbrage under the architecture of a fantasy, from where his trenchant political allegory could speak not only to his own time but seems to be speaking, too meaningfully for comfort, to our own too.

[1] Ray wrote the story and script of the last part Googa Baba Phire Elo (The Return of Googa Baba, 1992) which was about superstition, Tantrism and blind faith; but did not direct it, due to ill-health.

[2] Andrew Robison, The Inner Eye: The Biography of a Master Filmmaker, New Edition, IB Taurus, 2004; p 183.

[3] Ibid, p 183

[4] The child as an emissary of pure innocence is, in fact, the troubling plot of the third instalment of the trilogy, which is one of the key reasons for the severely weakened narrative of the film.

[5] I have written about Ray’s phenomenally popular sleuth and his imagined children in ‘Ageless Hero, Sexless Man: A Possible Pre-History and Three Hypotheses On Satyajit Ray’s Feluda’, South Asia Review, [Satyajit Ray Special Issue]; 36.1; pp 109-130. Routledge/T&F. 2015.

[6] See Daniel Yacavone, Film World: A Philosophical Aesthetics of Cinema, Columbia University Press, New York, 2015.

[7] Jack Zipes, ‘Why Fantasy Matters Too Much’, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Summer, 2009, 43:2, Special Issue on Children’s Literature, pp. 77-91; University of Illinois Press, p 78.

[8] It is no accident that a pair of ‘Plentimaw’ fish, who help weave stories and aid Haroun’s search is named Goopy and Bagha in Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories.

[9] Ian Almond ‘The Ghost Story in Mexican, Turkish and Bengali Fiction: Bhut, Fantasma, Hayalet, The Comparatist, Vol:41 (October, 2017), pp. 214-236; University of North Carolina Press, p 216.

[10] The ‘Dance of the Ghosts’ scene in Goopy Bagha, a stunning display of symbolic social histories revealed through gestural stratifications, is worthy of separate attention.

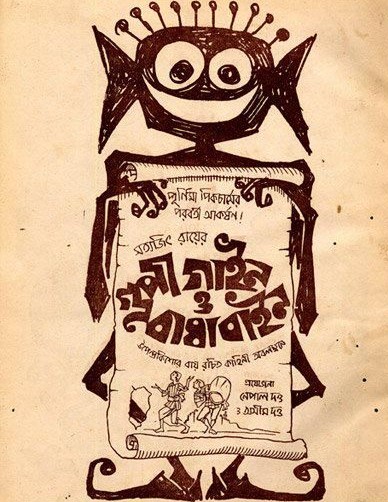

Essay image shows Satyajit Ray‘s poster of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, 1969.

comments for this post are closed