Taking the Mickey out of animation

Published @ Daily News & Analysis

There is a new graphic novel in town – Sarnath Banerjee’s The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, Steven Spielberg is producing a Tintin film, and noir director Anurag Kashyap is directing Hanuman 2. Suddenly, animation is threatening to grow up and rival adult live-action entertainment in a big way. Disney, Chandamama, and Superman creators Siegel and Shuster are in danger of being left behind for SFX, CGI, 3D, ‘comix’, manga, anime, graphic novel, and video games, as visual narratives ramify into widely varied, widely appreciated and widely influential modes of entertainment. Over the years, the comic element in comic strips has made way for serious, even grim issues — black humour, violence, the Holocaust, philosophical enquiry, absurd ideation and daily life.

Not that comics were not part of our life before; in fact, generations have grown up on a daily diet of Action Comics, Marvel Comics and D Comics superheroes. And the familiarity of Mufasa or Simba or that prickly cat and the naughty mouse or those Puranic legends of Amar Chitra Katha cannot be overestimated. But now, global markets have expanded. Thinking has exploded. Language has evolved. In India, for example, non-live action entertainment has travelled from producing two-minute social service snippets to full-length foreign features that are outsourced from India. Even a shoddy film like Hanuman did great business. And the industry is eagerly looking forward to a future of original possibilities. But where do these lie?

Sarnath Banerjee, whose Corridor was India’s first graphic novel, is defiantly against the homogenising tendencies of the mainstream, both in terms of its techniques, as well as its storytelling. “Mainstream methodologies have numbed our capacity for storytelling, be it a feature film, television or even traditional, orthodox animation. If you are looking for really authentic storytelling, look elsewhere,” he says. A contention that animation pioneer Ram Mohan partly agrees with. “Over the years, comics and animation have been burdened by Disney cuteness or social message burdens. We need to break free.”

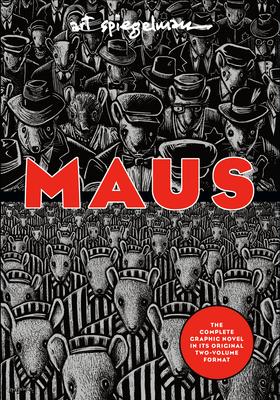

Ace animator Ajit Rao is also among those who share this thought. But while Rao and Ram Mohan would bet their money in the future of Indian animation, Banerjee would rather place his bets on comics. “I do not see much of a future in Indian animation. It’s still a borrowed language,” Banerjee insists. “But in comics and the graphic novel, new things are being explored, new languages are being learnt. In five years we might be in a position to look at a pantheon of mature work in this field in India. It may take a while for us to create the equivalent of Miller’s Sin City or Spiegelman’s Maus. But we might find a language of our own.”

Rao, on the other hand, is excited about the work of animators Gitanjali Rao (whose animation film Printed Rainbow won prizes at Cannes) and Animagic’s Chetan Sharma, who did the special effects for Eklavya. “They are doing fabulous work and need support. If the industry matures, animation has a big future in India,” says Rao. “But we must get out of the outsourcing model. Now, what we’re doing is mostly mechanical reproduction of art. There’s no creative impulse or original thought. Indians are a creative lot; they cannot just be assembly line designers.”

Kireet Khurana of 2nz animation disagrees. “Pixar and Disney have very creative people, but in large numbers. Creativity in animation is limited without collaboration and a critical mass. Often, those introducing gags into a script are ordinary artists, not the scriptwriter. So assembly-line production might teach us a thing or two about collaboration, working on big projects and the importance of little inputs.”

But what about the content? What is that ‘Indian’ idea that would breathe life into a narrative?

To get to an Indian subject is indeed a hard task, feel most animators, artists and writers. “If you are looking for really authentic storytelling go and search them in the Leather Puppetry in Karnataka, the Pats of Bengal or even carpets of Jaipur — which employ subtle and divergent ways of storytelling. But try telling that to entertainment executives and you face a wall”, says Sarnath Banerjee. This is indeed a problem with Indian animation. Lack of good ideas, good wholesome content. And there is that usual story: those with money peddle safe clichés, and those who have ideas are scouting for money. Kireet Khurana feels that Hanuman, a film about which he has lots of reservations, is still an important milestone. “It showed that an animation film with an Indian story and production values could sell. That was enough to invite other bigger producers to invest money. A lot depends on how the big-ticket animation productions from Aditya Chopra and BR Chopra banners do. The results will set the tone for a few years to come,” he hopes.

But is mythology and magic our only hope? Ajit Rao feels why not, even Walt Disney had to bank on them. “Disney was looking for content when he had kind of developed the technique and the first thing he fell back was on the fairy tales and fables. Only later did original characters come out. Mickey Mouse was inspired by the pantomime style of Charles Chaplin. That’s called evolution. We have to wait.” How long? Ram Mohan wants us to look at Japan’s Manga comics, something with a genealogy of its own. Says Ram Mohan, “we have just reached adolescence after years of being an animation infant. Now, we will grow fast.” For Khurana, however, it may be easier said than done. “How do you define Indianness in a global cultural matrix? So how do you develop Indian characters that would help sustain an industry?” he wonders. But Preet Bedi of Percept Communications, which produced Hanuman and is producing Hanuman 2, feels that a character like him is a perfect answer. “He is a secular hero. He is loyal, get things done, and is an energetic do-gooder – all the qualities of a comic-book protagonist. He can be a brand, ” he points out.

For Sarnath, the source of an Indian content lies not in traditional mythology, but urban mythology. “See, comics have always been a form of discontentment. Hence the days of superheroes are over. It’s time for people like you and me with their insane edges, own inanities, mysteries. Look at Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis for example.”

Rao feels that contemporary idiom is also hidden in various language comics and illustrations. “A character like ‘Bantul the Great’ is a masterpiece. It’s unadulterated fun — clean drawing, loud but Indian way of storytelling and more or less contemporary. But how many people know about the author Narayan Debnath? He already has created something many of us are looking for.”

All of them agree that exposure and interest in animation have increased manifold. And a new audience is in place — those who have grown up watching Cartoon Network for about a decade now. But no Indian producer would risk Disney or Pixar production values in Indian animation film. Whatever the beginning, clearly the Indian animation industry would still like to go the safer way. The forthcoming films– Magik, Hanuman 2, Krishnaleela, Dashavatar, Ghatothkach — do not attest to original stories though they might still be done well.

As for comics, Munnabhai and Circuit might find their dream of being in school test books realized as the producers of the film are toying with the idea of launching a comic series with the popular characters. Also, Virgin Comics is planning to launch a comic doppelganger of Sachin Tendulkar. Who knows, given his current form, he may end up finding immortality as a comic hero rather than a cricketing one.

But till that great Indian comic or animation hero emerges, adult lovers of non-live entertainment might like to stick to something like 300, the epical film adaptation of Frank Miller’s lusciously illustrated graphic novel about Spartan resistance against Persian occupation. Be it the textual version or the cinematic, something more profoundly graphic may not come out of India in many more years to come.

comments for this post are closed